The first brand in our new lineup was TCB Jeans, a company out of Kojima, Japan that builds its reputation on craftsmanship, historical research, and dedication to the original spirit of American denim.

Read More →

At Williamsburg Garment Company, we often receive jeans with requests to correct the work of other tailors or so-called denim specialists. Just because a tailor labels themselves as a denim specialist doesn’t mean they have the necessary expertise or use the right equipment. Moreover, owning a chain stitching machine is not synonymous with knowing how to use it correctly or understanding its intricacies.

Take these jeans as an example. Upon inspection, we discovered numerous issues with the chain stitching. Firstly, the thread tension was excessively high. Secondly, the sewing alignment was significantly off.

It’s possible they saw our article on how the roping effect is created by the seams not being aligned and overcomplicated the misalignment. Alternatively, it could just be a case of very sloppy sewing, resulting in the alignment being too far off and compounded by poor tension.

To further exaggerate the twisting, they likely didn’t press the hem. After washing, the fabric turned and puckered into this exaggerated form. Lastly, while the thread size might not directly cause the issue, its thinness and incompatibility with the original thread size only serve to highlight the problem.

We took these jeans and undid the previous poor hemming. Our team applied new chain-stitch hemming with precise alignment and appropriate thread tension, ensuring a smooth and professional finish. The corrected hem not only restored the jeans’ appearance but also maintained the integrity of the original design, as shown in the photo below.

When searching for a denim expert to work on your treasured jeans, the closest option may not be the best option. Check reviews, and most importantly, look at photos or examples of their work before deciding. Remember, just because someone has a chain stitching machine doesn’t mean they know how to use it properly.

The transformation from the poorly sewn hem to the expertly corrected one is a testament to our commitment to quality and precision. We understand the intricacies of denim and the importance of every stitch, ensuring that your jeans receive the care and expertise they deserve.

You might be interested in

If you’ve ever typed how to take in the waist of jeans into Google, you’ve probably seen a lot of

The first brand in our new lineup was TCB Jeans, a company out of Kojima, Japan that builds its reputation

The leg opening measurement is a critical factor in how your jeans fit over your shoes and shape your overall

Washing raw denim has long been a topic of debate. Some purists believe in waiting as long as possible, while

A Walk Through Denim History: A Closer Look at TCB Jeans

Our new collection from TCB Jeans features reproductions of two famous historical jeans models: the 1966 Levi’s 501, and the 1955 Levi’s 701. But what are historical reproduction jeans, and why does TCB focus on this approach to denim manufacturing? Here we’ll talk a bit about the history of the Japanese and American denim industries, the rise of TCB and their contemporaries, and the fascinating world of historical reproduction jeans.

The Origin Story: Levi’s Create an Icon

We can trace the history of denim back to one important date: May 20, 1873, when Levi Strauss and Jacob Davis obtained a patent for riveted work pants. Soon, they would produce their first pair of “waist overalls” from denim, a fabric commonly used for work pants at the time, and blue jeans were born.

Even this early, we can see in Levi’s waist overalls the essential details of modern jeans. They are made from denim, a “3×1” twill fabric woven in a repeated pattern where the interior weft thread runs three times over the exterior warp thread, then once under, producing a visible diagonal grain to the fabric. (To this day, the grain on Levi’s denim runs diagonally from the top right to the bottom left: a right-hand twill.) The warp thread is rope-dyed with indigo, leaving the jeans blue only on the outside—until they gradually fade to white, as indigo never fully penetrates the core of the cotton fibers. Metal rivets reinforce the pants at points of strain, a small watch pocket sits atop the main front-right pocket, and a rectangular patch on the back-right waistband features the company’s famous “two horses” logo.

Though at first unique to Levi’s, these details would be replicated and tweaked over and over again in other manufacturers’ jeans. The Levi’s patent on riveted work pants expired in 1892, opening the floodgates of jeans production to imitators and innovators alike, and Levi’s rushed to trademark what else they could: the two-horse logo in 1886, the Levi’s name in 1928, the red tab in 1936, and their iconic back-pocket arcuate stitching in 1943. By the mid-20th century, manufacturers were desperate to stand out from the crowd of Levi’s lookalikes, and its first major competitors emerged: Lee and Wrangler.

The Big Three: Lee and Wrangler Join the Fray

Levi’s’ dominance of the American denim market was disrupted by the emergence of Lee and Wrangler, who brought jeans from the gold mines to the ranch, the rodeo, and beyond. In the process, they introduced new design elements whose legacy is seen in historical reproduction and contemporary jeans alike—all while Levi’s developed their jeans into the “complete” model seen today.

Lee first hit the scene in 1913 with their “Union-Alls”, a one-piece coverall—the first of its kind—initially made for auto mechanics and later commissioned by the U.S. government to outfit soldiers in the First World War. Widely popular among the American working class, the Union-Alls’ success propelled Lee through the early 20th century until they released their true flagship garment in 1925: the Lee 101 jeans.

These jeans radically upended many of the details Levi’s had made synonymous with blue jeans—most notably, by flipping the twill pattern of the fabric to a left-hand twill, producing a distinct vertical fade pattern beloved to this day. Lee went on to develop several distinctive features of its own, creating the first zipper fly jeans, lightweight yet sturdy “jelt” denim, tailored waist and inseam sizing, “hair-on-hide” leather patches, and its unique acorn-shaped pockets with crosshatch corner reinforcements and “lazy S” curved stitching.

Lee’s massive popularity among cowboys and rodeo riders made them a westernwear staple, and their famous Buddy Lee mascot made them a national name. Once James Dean wore them in his legendary performance in the 1955 film Rebel Without a Cause, they were seared into film history and classic Americana alike. Levi’s had finally met their match—just in time for a third competitor to enter the fray.

Wrangler: broken twill, sanforized denim, flat-felled seams, exposed rivets, “W” pocket stitching, pocket patch, deep coin pocket, heavyweight denim,

Levi’s develops further: 1937, 1942, 1947, 1955, 1966

As denim transitioned from workwear to a cultural icon, Levi’s continuously innovated, mirroring broader societal shifts and technological advancements. Key milestones in their product development reflect these changes.

In 1937, responding to a burgeoning economy and consumer feedback, Levi’s introduced jeans with concealed rivets on the back pockets. This modification addressed complaints about rivets scratching furniture and saddles, showcasing the brand’s early commitment to customer satisfaction and the evolving role of jeans beyond purely work attire.

With the United States’ entry into World War II in 1941, Levi’s faced new challenges. The government’s rationing policies during the war years led to adjustments in 1942, such as the removal of the cinch back and the introduction of painted-on arcuates and pocket stitching to conserve thread and materials. These changes highlighted Levi’s resilience and ability to innovate under restrictive conditions.

By 1947, post-war prosperity and a return to peacetime manufacturing allowed Levi’s to reinstate the iconic stitched arcuate design on the pockets, bringing back features removed due to wartime restrictions. This era marked a return to the “classic” jeans, emphasizing quality and durability that resonated with a wide range of consumers.

The introduction of a more relaxed fit in the 1955 model reflected the casualization of American fashion and the rise of the youth market. This version offered comfort without compromising durability, appealing to the growing demographic of teenagers influenced by jean-wearing film icons like James Dean and Marlon Brando.

In 1966, Levi’s unveiled the orange tab as a symbol of its fashion-forward line, distinct from the traditional red tab workwear products. This innovation targeted different consumer segments, acknowledging the diverse ways jeans were being embraced and perceived across cultures.

Through these pivotal years, Levi’s didn’t just respond to consumer demand and societal trends; it helped shape the cultural significance of denim. Each model evolution was a testament to the brand’s understanding of the times— from practical wartime adjustments to meeting the fashion sensibilities of a burgeoning post-war youth culture. Levi’s capacity to evolve while upholding its reputation for quality and durability underscores its enduring influence in the denim industry.

Occupation and Trade: Denim Comes to Japan

The introduction of denim to Japan in the aftermath of World War II is a fascinating story of cultural exchange, economic innovation, and the transformative power of fashion. As American GIs occupied Japan, they brought with them not just the might of the United States military but also the casual, rugged style of American workwear, most notably jeans, which would eventually become a symbol of rebellion, freedom, and fashion around the world.

Initial Introduction:

The immediate post-war period saw the first influx of denim into Japan through various means. Hank-dyed indigo fabric, prized for its depth of color and character, caught the attention of the Japanese, known for their appreciation of detailed craftsmanship in textiles. The American occupation forces inadvertently introduced jeans to the Japanese public, with surplus and used jeans finding their way into the Ameyoko black market in Ueno, Tokyo, through shops like Hinoya and Americana. This period also saw the emergence of “Pan Pan girls,” young women who, in the dire economic straits of post-war Japan, sometimes accepted jeans as payment for sexual services, highlighting the high value placed on this foreign commodity. The term “jii-pan” (a Japanization of “jeans”) began to circulate, marking the beginning of Japan’s enduring fascination with denim.

Cultural Exposure:

The cultural impact of denim in Japan was further amplified by American films such as “The Wild One” and “Rebel Without a Cause,” which featured charismatic protagonists clad in jeans, epitomizing a new, rebellious youth culture. These films, along with the “Taiyōzoku” (Sun Tribe) subculture—a Japanese youth movement that embraced a hedonistic lifestyle influenced by the portrayal of rebellious American youth—helped cement the status of jeans as a symbol of youthful defiance. The Shinjuku movement, centered around Tokyo’s Shinjuku district, became a hub for this burgeoning youth culture, further integrating jeans into the fabric of Japanese society. Additionally, the practice of vintage sourcing from America began to take root, with enthusiasts seeking out authentic American denim to satisfy a growing demand.

Economic Development:

The fascination with denim soon translated into economic opportunity. Japan’s textile industry, seeking to replicate the quality and appeal of American denim, began its own production. The use of Toyoda shuttle looms, which could produce denim with the selvedge edges that were a hallmark of quality, was a critical step in this process. Kurabo Mills introduced the KD-8, the first selvedge denim woven in Japan, marking a significant milestone in the domestic production of high-quality denim. Brands like Big John capitalized on this development, launching the M-series jeans, which were among the first made-in-Japan denim products to gain widespread recognition. Other mills, such as Kuroki, Collect, and Japan Blue in Kojima, further advanced the craft, refining techniques and materials to create denim that rivaled, and in some aspects surpassed, its American counterparts. This period of economic development was not just about replicating American denim but also about innovating and establishing a unique identity for Japanese denim on the global stage.

The Second Wave: The Osaka Five Revive History

The “Osaka Five” is a term that encapsulates the pioneering spirit of five Japanese denim brands: Studio D’Artisan, Denime, Evisu, Full Count, and Warehouse. These brands, emerging in the late 1980s and early 1990s, marked a renaissance in the world of denim, igniting a “Second Wave” of interest in high-quality, vintage-inspired jeans. Their collective efforts not only revived historical denim production techniques but also set new standards for quality and authenticity in the industry.

Studio D’Artisan: Founded in 1979, Studio D’Artisan is credited with being among the first to ignite the vintage denim revival in Japan. Known for its intricate, artisanal approach to denim, the brand recreates the feel and look of American jeans from the 1930s to the 1960s, paying meticulous attention to fabric, fit, and finish. Their use of selvage denim, combined with traditional dyeing techniques, sets a benchmark for quality.

Denime: Launched in 1988, Denime sought to reproduce the iconic Levi’s jeans of the 1950s and 1960s, focusing on the details that denim aficionados cherish. Denime’s dedication to recreating the texture and feel of vintage denim has earned it a loyal following, with particular praise for its replication of the famous Levi’s 501XX model.

Evisu: Initially named Evis after the Japanese god of prosperity, Evisu burst onto the scene in 1991 with a mission to create jeans that would rival the quality of Levi’s vintage 501s. Famous for its hand-painted seagull logo on the back pockets, Evisu uses traditional methods, including loop dying, to achieve a depth of color in its denim that is reminiscent of the past.

Full Count: Full Count, founded in 1992, distinguished itself by using Zimbabwe cotton, renowned for its long fibers, to create jeans that are incredibly soft yet durable. The brand focuses on the 1940s to 1960s era of jeans, with particular emphasis on the 1955 model of Levi’s, ensuring that every detail, from the rivets to the stitching, is historically accurate.

Warehouse: Warehouse completes the Osaka Five, offering jeans that are celebrated for their historical accuracy and quality craftsmanship. Warehouse’s dedication to the recreation of 1930s to 1960s denim includes a focus on raw denim, which ages and fades uniquely to each wearer, as well as the use of natural indigo and attention to the distinctive “leg twist” feature resulting from the traditional right-hand twill weaving process.

The Osaka Five’s collective dedication to reproducing historical jeans extends beyond mere aesthetics. Each brand focuses on specific years or eras, replicating the original fabrics as closely as possible. This includes sourcing raw denim that mirrors the original weights and textures, employing natural indigo dyeing methods for authentic coloration, and embracing the leg twist characteristic of vintage jeans created on shuttle looms. These brands’ efforts to capture the essence of historical denim have made them revered names among denim enthusiasts worldwide, ensuring that the legacy of vintage jeans continues to inspire and influence modern fashion.

Historical Reproduction in the Modern Day: TCB and their Contemporaries

The contemporary landscape of Japanese denim is marked by an impressive dedication to the art of historical reproduction, with brands like TCB and their contemporaries leading the charge. These labels stand out for their commitment to authenticity, craftsmanship, and the meticulous recreation of vintage denim’s look, feel, and spirit.

TCB Jeans: Standing for “Two Cats Brand,” TCB has carved a niche in the denim world with its faithful reproductions of mid-20th-century American jeans. The brand is known for its attention to detail, from fabric to fit, using vintage sewing machines and techniques to achieve an authentic vintage look. TCB’s offerings, such as replicas of the 1950s and 1960s Levi’s models, are celebrated for their craftsmanship and authenticity, embodying the essence of the eras they represent.

Ooe Yofukuten: A smaller, artisanal brand, Ooe Yofukuten is renowned for its limited-run denim productions that emphasize quality and historical accuracy. Each pair of jeans is meticulously crafted, reflecting the brand’s passion for denim’s heritage. Ooe Yofukuten specializes in reproducing rare and lesser-known models from the early to mid-20th century, offering enthusiasts a taste of denim history that is seldom found elsewhere.

One Piece of Rock: This brand stands out for its unique approach to denim reproduction, focusing on the cultural and musical influences on denim fashion over the decades. One Piece of Rock produces jeans that not only replicate the fabrics and fits of historical pieces but also embody the spirit of the times they represent, from rock ‘n’ roll to the counterculture movements.

The Real McCoys: With a broader focus on Americana and military wear, The Real McCoys extends its commitment to authenticity to its denim line. The brand is lauded for reproducing iconic American garments, including jeans that are as close to the original specifications as possible. The attention to detail, from the cotton blend to the dyeing process, ensures each pair of jeans is a testament to denim’s enduring legacy.

Sugar Cane: Famed for its innovative use of sugar cane fiber blended with cotton, Sugar Cane jeans offer a unique texture and natural fading pattern. The brand excels in creating denim that not only harks back to vintage aesthetics but also introduces sustainable materials into the classic manufacturing process, offering a modern twist on historical reproductions.

Buzz Rickson’s: While Buzz Rickson’s is primarily known for its military reproductions, its venture into denim captures the rugged, durable essence of workwear that characterized early jeans. By focusing on the utilitarian aspects of denim and reproducing models worn by military personnel, Buzz Rickson’s adds a layer of historical significance to its jeans.

Toys McCoy: This brand seamlessly blends pop culture and denim history, reproducing jeans that have become icons in film and television. Toys McCoy’s dedication to replicating the denim seen on screen extends to the minutest details, making their jeans a collectible piece of cultural history.

Together, these contemporary Japanese brands contribute significantly to the preservation and celebration of denim’s rich history. By focusing on historical accuracy, quality craftsmanship, and the stories that vintage denim tells, they ensure that the legacy of iconic jeans continues to be worn and appreciated by generations to come.

American Revivalism: Levi’s Vintage Clothing, Lee Archives, and RRL

Under the banner of “American revivalism,” several heritage and premium labels have taken significant strides in bringing the rich history of denim to the modern wardrobe, faithfully replicating vintage styles that capture the essence and nostalgia of bygone eras. Among these, Levi’s Vintage Clothing, Lee Archives, and RRL stand out for their dedication to authenticity, craftsmanship, and the preservation of denim culture.

Levi’s Vintage Clothing (LVC): LVC delves deep into Levi Strauss & Co.’s extensive archive to recreate historic pieces with an unparalleled level of detail. This line is a homage to Levi’s storied past, bringing to life the jeans that defined different eras, from the rugged 501s of the 1890s to the slim fits of the 1960s. LVC doesn’t just replicate the cuts and styles of these periods; it also uses manufacturing techniques and materials that mirror the originals, including selvedge denim woven on vintage shuttle looms and natural indigo dyeing processes. Through LVC, Levi’s offers not just a piece of clothing but a tangible slice of Americana, inviting wearers to step directly into the shoes of gold miners, cowboys, and rebels of the past.

Lee Archives: Lee Archives takes a similar approach, diving into the rich history of the Lee brand to bring back the jeans, jackets, and workwear that made it a household name. Focusing on key periods in the brand’s history, the Archives collection reproduces the iconic pieces that helped shape the denim industry, such as the 101J denim jacket and the 101Z jeans with their distinctive zip fly. By maintaining the original specifications, including the use of left-hand twill denim and the introduction of unique details like the Lazy S stitch, Lee Archives not only celebrates the brand’s innovation and influence but also provides a window into the evolution of denim fashion.

RRL by Ralph Lauren: Named after Ralph Lauren’s Double RL ranch in Colorado, RRL draws inspiration from the American West and vintage military uniforms, translating them into high-end, vintage-inspired collections. While not solely focused on denim, RRL’s approach to jeans is notable for its commitment to authenticity and quality. The brand utilizes selvedge denim, much of it woven on vintage looms, and employs aging and distressing techniques that give each piece a uniquely worn-in feel. RRL jeans are a testament to the enduring allure of American workwear, reimagined for a contemporary audience that values the craftsmanship and story behind their clothing.

Together, Levi’s Vintage Clothing, Lee Archives, and RRL represent the pinnacle of American revivalism in denim. Through their efforts, these brands not only preserve the legacy of iconic denim styles but also continue to inspire and influence the trajectory of denim fashion, blending history with modern sensibility in each meticulously crafted piece.

The future at home and abroad

With a refined lens on the burgeoning nodes of denim evolution, it’s evident that both new and established names are weaving the future tapestry of this timeless fabric. The emergence and growth of entities like the White Oak Legacy Foundation, Vidalia Mills, and an array of dedicated studios and brands, from Ridgewood, Queens to Brooklyn, NY, and across the Pacific to Japan, herald a vibrant era for denim, characterized by an unyielding commitment to craftsmanship, sustainability, and innovation.

In Ridgewood, Queens, Todd Martin Studio emerges as a crucible of denim creativity, where each pair of jeans is not just crafted but born out of a dialogue between artisan and fabric. This studio exemplifies the potential of hands-on, personalized denim making, offering bespoke jeans that mirror the wearer’s ethos and style. Nearby, First Standard Co. echoes a similar commitment to denim’s legacy and its future, blending timeless designs with modern ethical practices. Their approach underlines the importance of locality in the global denim narrative, grounding their craft in the community and culture of Ridgewood.

Over in Brooklyn, Bowery Blue Makers channels the borough’s industrial past and vibrant present into its denim. Operating with vintage machines and techniques, the brand crafts jeans that narrate the city’s relentless spirit, a testament to New York’s enduring influence on the denim landscape.

Across the waters in Japan, Bridge Of The Times stands as a testament to the individual passion and global impact possible in today’s denim world. Founded in 2020 by Masatoshi Takenaga, this one-man brand encapsulates the essence of innovation and cross-cultural dialogue in denim. Takenaga’s work is a blend of meticulous Japanese craftsmanship and a keen eye for contemporary design, bridging eras and geographies with each piece he creates.

Together, these entities — from the preservation efforts of the White Oak Legacy Foundation to the innovative production at Vidalia Mills and the artisanal excellence of studios in New York and Japan — illustrate a dynamic future for denim. This future is not confined to the boundaries of tradition or the limits of current fashion trends. Instead, it’s a broad, inclusive vista where sustainability, artistry, and global collaboration intertwine, ensuring that denim remains as relevant and revered tomorrow as it has been for over a century.

Check out these other sources for more information

Heddels – “A Brief History of Lee Jeans”

Heddels – “A Brief History of Wrangler Jeans”

Heddels – “Levi’s – History, Philosophy, and Iconic Products”

Heddels – “Who Made Japan’s First Jeans?”

Lee – “The History of Lee Jeans”

Lee – “The Union-All Legend”

Redcast Heritage – “History of Japanese Denim”

—

When it comes to denim, there’s a rich tapestry of history woven into every thread, every seam, and every wash that tells a story. For the denim aficionado, there’s nothing quite like the charm of vintage jeans – each pair a slice of history, a narrative of style through the ages. But vintage finds are rare, sizes are limited, and the hunt can be exhaustive. Enter the world of reproduction jeans, where history is not just preserved but is recreated with an attention to detail that’s almost reverential.

What Exactly Are Reproduction Jeans?

Reproduction jeans are not your run-of-the-mill retro-inspired denim. They are a meticulous re-creation of historical jeans, crafted with the aim of capturing the essence, fit, fabric, and even the idiosyncrasies of the original pieces. These are jeans born out of a passion for denim heritage, made for those who appreciate the subtleties that distinguish a 1940s cinch back from a 1950s selvedge.

TCB Jeans: Crafting History with Every Stitch

TCB Jeans stands out as a torchbearer in the realm of reproduction denim. The brand takes its name from ‘Two Cats Brand,’ a homage to the feline friends of the company’s founder. But it’s not just the name that’s imbued with character – every pair of TCB jeans is a narrative piece, telling the story of a bygone era through its fabric and construction.

The commitment of TCB Jeans to authenticity goes beyond the surface. From sourcing the right kind of cotton to using vintage machines for production, every aspect of the manufacturing process is considered and executed with the utmost fidelity to the originals. The result? Jeans that don’t just look vintage but feel it, too.

The Allure of TCB’s Reproduction Jeans

Imagine slipping into a pair of jeans that transport you to the 1950s, the golden age of denim. TCB’s 50s jeans do just that. With their high-waisted, straight-leg cut, they embody the comfort and style of the era – designed not just for looks but for life. The charm is in the details: the selvedge, the stitching, the cut, all speaking the language of authenticity.

Why Choose Reproduction Jeans?

Reproduction jeans like those from TCB are more than just clothing; they’re collectibles, pieces of wearable art that pay respect to the denim legends of the past. They offer the chance to own a piece of history without the wear and tear of decades. For anyone who values the narrative of their clothing, reproduction jeans are a way to connect with the past while enjoying the quality and comfort of the present.

Embracing the Past with TCB Jeans

As TCB Jeans continues to stitch the past to the present, it invites denim enthusiasts to explore its collection. Each pair of jeans is a testament to the labor of love that goes into crafting reproduction denim. It’s an invitation to not just wear a pair of jeans but to live a story, to walk in the footsteps of the icons that made denim the timeless symbol of style that it is today.

Ready to embark on a journey through denim history? Shop TCB Jeans or find out more about the intricate craft of creating jeans that are as authentic as they are timeless. Discover your own slice of the past, tailored for the present, with TCB Jeans.

You might be interested in

If you’ve ever typed how to take in the waist of jeans into Google, you’ve probably seen a lot of

The first brand in our new lineup was TCB Jeans, a company out of Kojima, Japan that builds its reputation

The leg opening measurement is a critical factor in how your jeans fit over your shoes and shape your overall

Washing raw denim has long been a topic of debate. Some purists believe in waiting as long as possible, while

Nick English of Stridewise dropped by our 67 West Street studio in the heart of Greenpoint, Brooklyn, entrusting us—the nation’s top-tier denim alteration specialists—with refining the fit of his jeans at the waist. Dive into our expert process through this video, and if you’re plotting a course to our doorstep, we’ve included some handy navigation tips to guide you right to us.

Don’t miss Nick’s website, where he explores boots and other gear. For denim enthusiasts, there’s a must-read post titled ‘Best Selvedge Denim.

You might be interested in

If you’ve ever typed how to take in the waist of jeans into Google, you’ve probably seen a lot of

The first brand in our new lineup was TCB Jeans, a company out of Kojima, Japan that builds its reputation

The leg opening measurement is a critical factor in how your jeans fit over your shoes and shape your overall

Washing raw denim has long been a topic of debate. Some purists believe in waiting as long as possible, while

Jeans and pants are a part of our everyday lives, and there’s more to them than just the fabric. Have you ever thought about the seams? They play a big role in how your jeans and pants look, feel, and last.

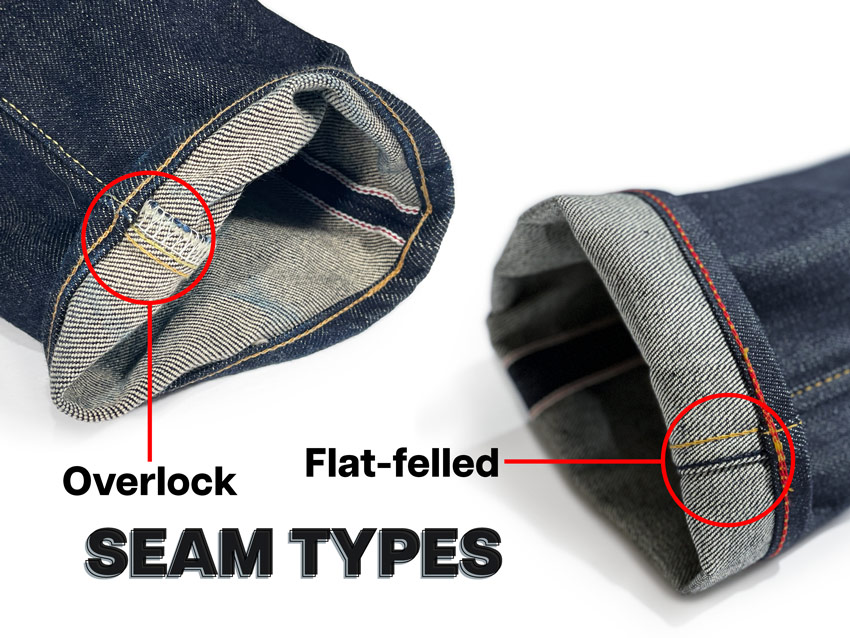

Excluding tailored clothing which is generally a single lockstitch with merrow stitching or binding over the edges, the two main kinds of seams in jeans and similarly constructed pants are flat-felled and overlocked seams.

If you’re thinking about tailoring your jeans or pants (especially tapering) or just want to know more about fashion, it’s good to understand these seams. Why? Because each seam type comes with its own set of benefits and challenges that can significantly affect the alteration process, durability, and aesthetics.

Flat-felled vs. Overlocked seams

Flat-felled seams are the most common type of inseam construction on jeans and similarly constructed pants. They are created by folding the raw edges of the fabric over, and on themselves, then stitching them together. This creates a strong and durable seam that is also very flat and neat. These seams are celebrated for their durability, fray resistance, clean finish, and aesthetic value. Flat-felled seams are often used on high-quality jeans in the light-to-midweight fabric range but can be a problem with heavyweight or thick fabrics because of the multiple layers of folded fabrics required to sew through where seams meet and the fabric’s weight.

When it comes to sewing through multiple seams, manufacturers of heavyweight denim will use flat-felled seams at the seat, even though they must sew through 12 layers of fabric where the yoke and center seat seams meet, and avoid the flat-felled seam on the inseam, where 8 layers of fabric must be sewn through in the crotch, for several reasons.

First, in the seat area of jeans and similarly constructed pants, the flat-felled’s low profile, smoothness, and visual aesthetic have more value than an overlocked seam. Second, because of the shorter distance regarding sewing, errors can be more quickly corrected compared to the long distance at the inseam.

Some brands, such as Bravestar and a few others, will take on the massive challenge of producing heavyweight jeans with flat-felled inseams. Sewing flat-felled inseams of heavy jeans during tapering is tough in our experience, not because of the fabric’s thickness, but due to the weight and gravity pulling on the jeans while they hang under the off-the-arm sewing machine. The weight exerts a continual tug on the fabric, which the sewer is attempting to hold upward into the folder, which causes the fabric edges to turn over, to create flat-felled seams. Shorter sewing distances, such as the rear yoke and center seat seams, are not a problem. Longer sewing distances, such as the inseam, have three to four times the weight and force pulling the fabric down and out of the folder. As a result, every time the sewer adjusts their hand position while sewing, the fabric slips down, or lower in the folder, causing sewing problems. This is most certainly the most significant explanation for why factories prefer to produce heavyweight jeans with overlock inseams.

Overlock seams, also known as serged seams, are another common type of inseam construction. These are generally used on the insides of the garment. Overlock seams are created by an overlock machine, which stitches the seam, trims the seam allowance, and encases the edge of the fabric with thread, all in one step.

The overlocked seam is more valued at the inseam on heavyweight jeans because it’s easier to sew. Also, it does not create as much bulk where the seams meet in the crotch, where there is lots of movement, unlike the yoke area of the seat, which sits flat. Lastly, the more unsightly appearance of the overlock seam is not visible on the inseam unless the jeans are turned up at the hem.

While not as durable or aesthetically pleasing as flat-felled seams, overlock seams are quicker and more economical to produce. They also provide adequate fray resistance, which is particularly important on the raw edges of denim.

The Importance of seam type in Tapering Jeans and Pants

What does this have to do with getting your pants and jeans tapered? To begin with, the type of seam influences the method and difficulty of making an alteration. The vast majority of tailors will taper jeans and pants from the outseam to avoid the inseam because of a lack of equipment, knowledge, or both. This is not an option with selvedge clothing since it would damage the selvedge. Unless flared, or garments designed for curvy bodies, the shape of jeans and pants legs is typically drafted in the inseam, leaving the outseams mostly straight up to the hips. As a result, modifications should also be made to the inseam.

Tailoring flat-felled seams requires a feed-off-the-arm sewing machine to be done correctly, and in order to maintain the original construction. It also requires skill and knowledge of the construction techniques used on mass-produced read-to-wear garments, which often have very different rules than tailored clothing.

Overlock seams, on the other hand, are easier and faster to alter. An overlock machine, which is one of the more common types of sewing machines available in many types of tailoring establishments, can be used to cut and re-sew the seam. Most tailors will struggle with how to handle the top stitch that is sewn on top of overlocked seams. Without an off-the-arm machine, it’s impossible to sew a fresh top stitch from hem to hem in a single pass, without taking the garment apart. Because they can only sew so far up the leg, heading upward towards the crotch, they must either link a new top stitch to the previous one. Alternatively, they can open the outseams all the way to the hips in order to fit the jeans or pants through a flatbed machine, sewing around the inseam, in a single pass.

In Summary

Choosing to taper your jeans can give them a fresh lease of life, adapting them to changing trends or personal style preferences. But before you take them to a tailor, examine the inseam construction. Knowing whether you’re dealing with a flat-felled or overlocked seam will help you understand the complexity of the task and manage your expectations regarding cost, time, and final appearance. This way, you’ll ensure you’re making an informed decision about tailoring, helping your favorite denim remain a staple in your wardrobe for years to come.

You might be interested in

When it comes to buying jeans—especially online—getting the right inseam measurement is crucial for a proper fit. Whether you’re checking

Got a twisted leg on your jeans? If one leg seam always seems to drift to the front or back,

Why the Same Inseam Length May Lead to Different Results

When it comes to hemming pants, maintaining the original look is key. Many tailors use what’s known as an “original

Summary

Jeans hemming is the process of shortening the leg or inseam length of a pair of jeans by removing some of the fabric from the bottom.

These photographs demonstrate the before and after effects of hemming alterations made by Williamsburg Garment Company to shorten the inseam of jeans to demonstrate “what jeans hemming is.” The top photograph features a pair of Pure Blue Japan jeans. It displays the altered inseam and leg openings as well as the portions of the hem that was removed.

The below image displays a pair of raw denim jeans with their original hem and full inseam length. A chalk line on the jeans marks the hemming cut line, which also includes a 1/2-inch double fold (1-inch).

The majority of jeans are sewn with chain-stitched hemming. The average hem measures roughly 1/2 inch tall. A tailor or seamstress double folds the raw edge after cutting to the hem (leg opening). Since each fold measures approximately 1/2 inch, the inseam length must be increased by 1 inch to reach the desired length.

To see what we mean by double folding, and the process of hemming in action. Watch our video “Chain Stitch Hemming in 87 Seconds.”

Chain Stitch Hemming in 87 Seconds

You might be interested in

If you’ve ever typed how to take in the waist of jeans into Google, you’ve probably seen a lot of

The first brand in our new lineup was TCB Jeans, a company out of Kojima, Japan that builds its reputation

The leg opening measurement is a critical factor in how your jeans fit over your shoes and shape your overall

Washing raw denim has long been a topic of debate. Some purists believe in waiting as long as possible, while

So you splurged on that vintage-looking pair of Gap 1969 jeans. They are everything you were looking for, but about 4-to-5-inches too long. Now what? You don’t want to wear them rolled with a huge cuff – or even have them stacking over your shoes. You want to make them one of your go-to jeans, so you need them to fit right. Here’s how you can make that happen: With fast professional chainstitch denim hemming service that’s available from any city or town in the USA! We make our alterations services simple and both affordable and easy to execute. Read on to learn how we can help you achieve the perfect fit:

What is a Chainstitch Hem?

A chainstitch hem is a technique used in most jeans. It’s a fairly common and durable stitch that is found on most jeans. As seen on the above pair of Gap 1969 jeans, you’ll want to ensure when shortening your inseam, the jeans have the same style of sewing as the original store-bought jeans. That’s with chain stitching and thick, heavy threads. Both are not options not usually found at local tailors, cleaners, and even department stores or a brand’s in-store alterations services. Read more on chainstitch hemming on our blog.

How to order Hemming from us

We receive and ship altered jeans, pants, and shirts from all over the USA. Sometimes, those seeking the very best denim services will ship us garments from other countries. We offer low-cost 2-way shipping options, so you can ship 1 or multiple items in an order for the same low price. With 2-way shipping, we email you a shipping within a few hours of placing your order, or the next morning when ordering after business hours.

Additional Rush Alterations Options to Consider

We offer RUSH and STANDARD SERVICE. The fastest is Same-Day while you wait. The next fastest is 1-Day Service. Our regular service takes about 5-to-7 days. Pricing for all services is listed on the ordering page.

The Catch-22 of Denim Hemming

Unfortunately, there are DIY techniques and non-professional denim tailors who offer what’s called an Original Hem alteration. They say you can retain the original pre-washed edge on the leg opening, but they don’t tell how bad your jeans will look on the inside or how you will lose the flexibility of the hem.

Final Words

Original hems are a bad idea. Don’t let anyone talk you into this style of alteration. We get lots of jeans sent to us with requests to undo this alteration and re-hem the jeans correctly with chain stitching.

The pre-washed edge on the leg opening, as seen on the section cut from Gap 1969 jeans comes back in time with washing and wearing. If you want to speed up the process, you can rough up the hem with sandpaper, a sharp blade, or an electric grinder for the shredded look. For fast fading, wet and wrinkle the hem, then rub in a small amount of bleach on the high points, and dip the hem in cold water to halt the fading. Machine wash the jeans after.

You might be interested in

If you’ve ever typed how to take in the waist of jeans into Google, you’ve probably seen a lot of

The first brand in our new lineup was TCB Jeans, a company out of Kojima, Japan that builds its reputation

The leg opening measurement is a critical factor in how your jeans fit over your shoes and shape your overall

Washing raw denim has long been a topic of debate. Some purists believe in waiting as long as possible, while